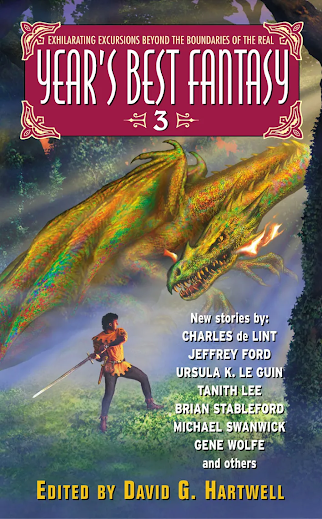

So let's see what other wonders this book of "the best" fantasy stories of 2002 has for us.

"A Book by Its Cover" by P.D. Cacek - In Nazi Germany, shortly before the Holocaust begins in earnest, a Jewish bookshop owner finds his store, which the Nazis had raided and burned all his books, can turn people into a copy of their favorite book, from which state they can be recalled. He uses this to help Jews escape the e-e-e-evil Nazis.

I found this story annoying at first, but after a while, it was actually pretty funny. Once you've grasped that the event in question simply did not happen, the propaganda about it can be humorous. In this case, you have to accept that the Germans this boy knew, for no reason at all, became seized by an insane hatred. They are literally cartoonishly evil. The author does not have the main character's former friend, now Nazi, actually twirl his mustache while cackling maniacally, but he may as well have.

The only reason stories like this get by is because they are coasting on a huge swell of emotional manipulation. But if you're free of that, it's quite funny how empty they are.

"Somewhere in My Mind There Is a Painting Box" by Charles de Lint - Holy crap! It's an actual, unambiguous fantasy story...and there's not some wicked political message thinly disguised...and it feels like a fairy tale, with the same kind of dangers of fairy land that stories all the way back to the brothers Grimm might warn of. I'm shocked.

Good story. This is the first good unambiguous fantasy story I've seen here so far, and I'm almost a quarter of the way through the book.

"The Pyramid of Amirah" by James Patrick Kelly - Fantasy? Check. Good? It's interesting and well-written, at least. For a late-twentieth century atheist, this is a pretty good take on religion. So, yeah, it works.

"Our Friend Electricity" by Ron Wolfe - A middle-aged low-level book editor has a whirlwind romance mostly at Coney Island with a pretty twenty-ish young woman. The main character may murder someone with a skee ball. Near the end, he either has a vision of the past or travels back in time briefly for no clearly explained reason.

There are some genuinely poetic passages here, but by the end, it feels self-indulgent, writers writing about writers, for one thing. Also, the "fantasy" element enters late, and is vague and poorly integrated with the rest of the story. This is not a bad story, but it's terrible fantasy.

Again, I grow weary of being sold "It might be fantasy if you squint and look at it from a certain angle." Writers and editors, if you don't want to write fantasy or science fiction, that's fine. You don't have to. Don't write it. But please do not write mundane "literary" fiction, barely dress it up, and try to sell it to me as "fantasy."

I am now about 1/3 of the way through this book and I have found 2 stories, only 2, that are actually good, and actually fantasy. I get the impression Hartwell knows better and I can only attribute this disaster to the co-editor Kathryn Cramer.

Hmmm, Cramer? Oh, every single time.

I will soldier on and complete this review, possibly by the end of this year.